Fewer Boats, More Fish

Posted by Dale Squires

September 30, 2015

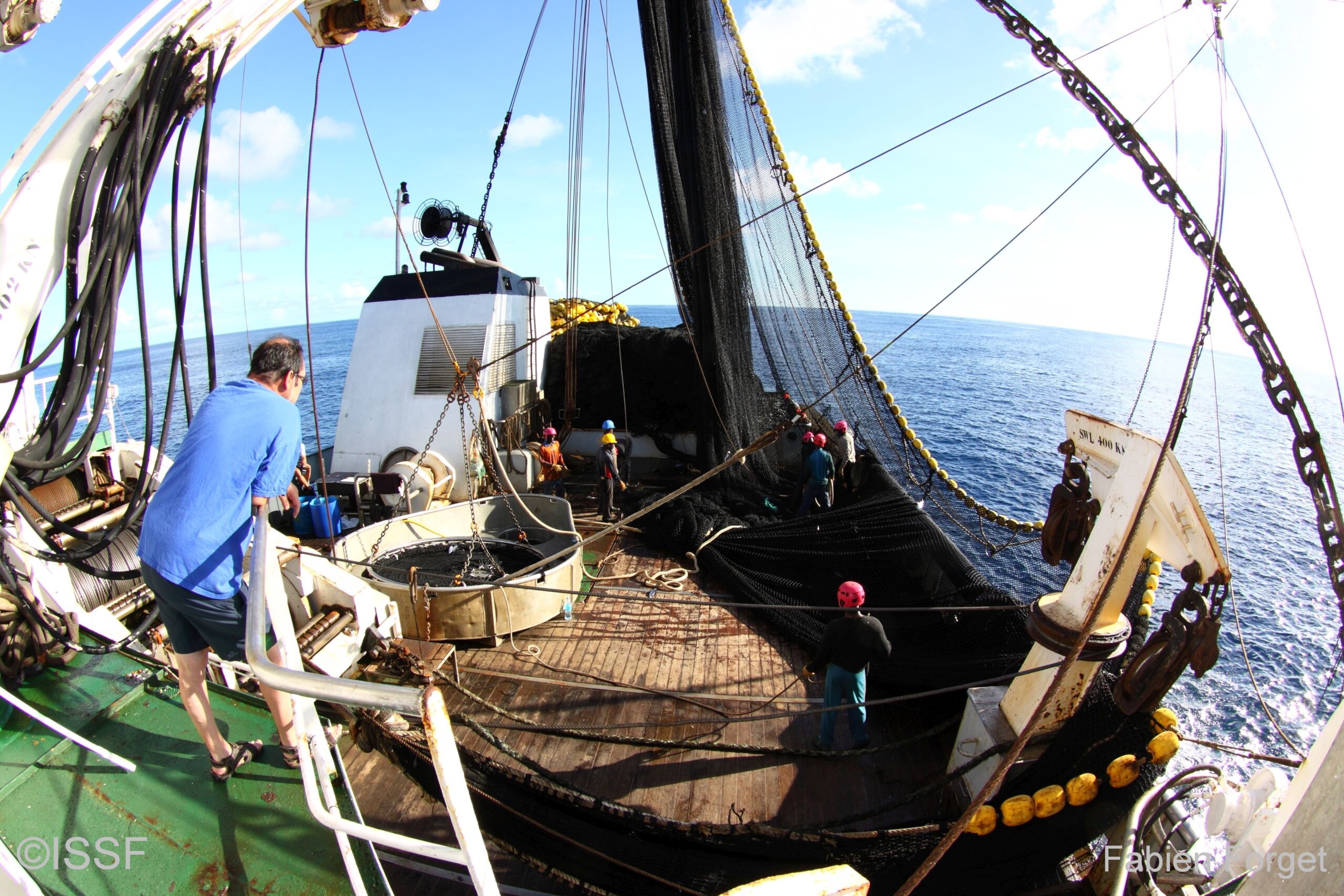

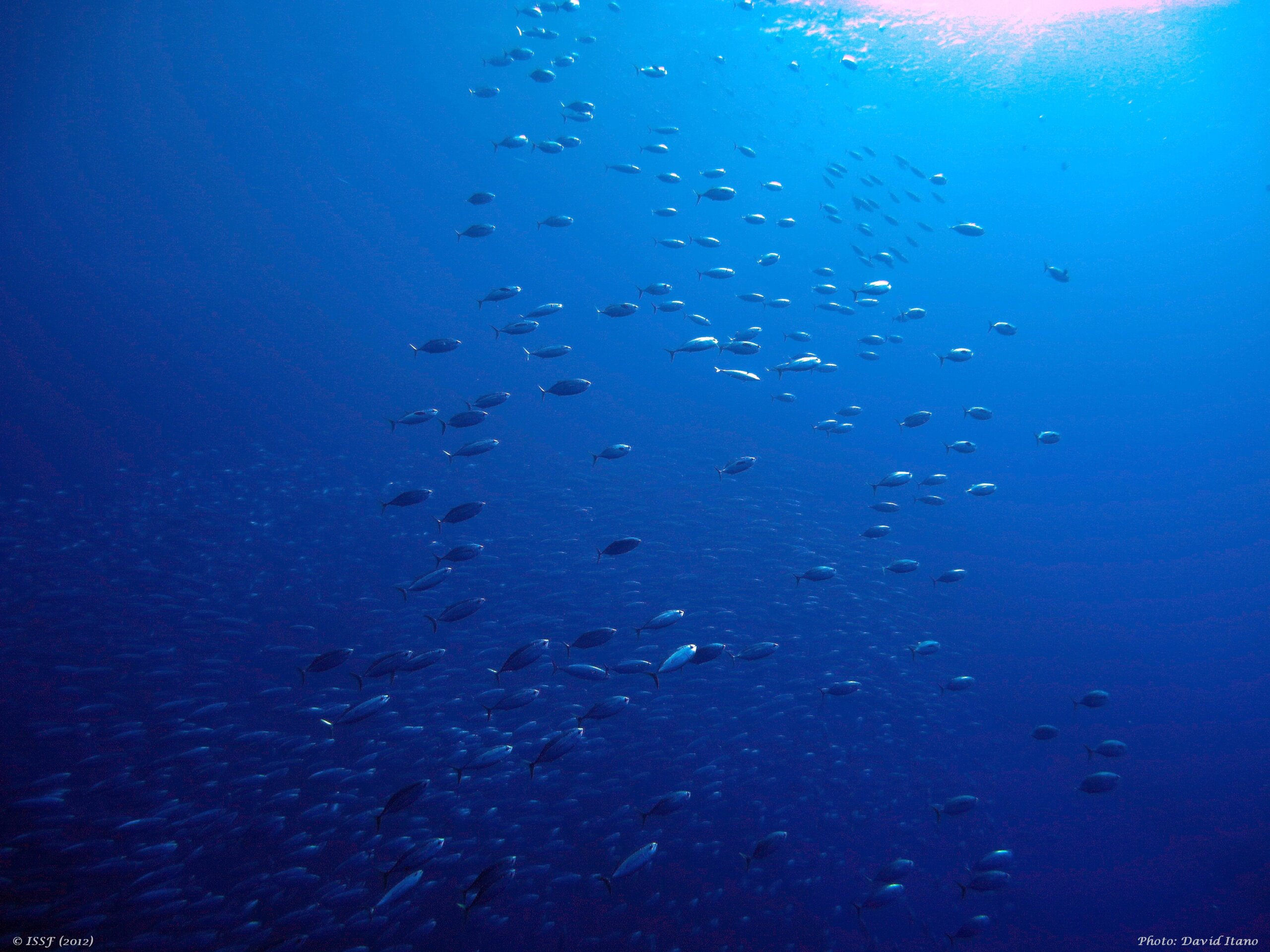

Fishing capacity is the amount of fish or fishing effort that can be produced over a period of time (i.e. one year or a full fishing season) by a vessel or a fleet if fully utilized. Proper capacity management seems like a simple enough concept: have fewer boats on the water so that pressure on tuna stocks relents to a more ideal level. If you could only explain it in one sentence, that might just be the best way to do it; however, like all issues associated to managing fisheries, we don’t have the luxury of simplicity, which is why I’m glad I have the opportunity to say more than a sentence about how we, as conservationists and scientists, can continue to move the needle to limit fishing capacity across all tuna fisheries to more sustainable planes.

The 1999 FAO International Plan of Action for the Management of Fishing Capacity notes that excessive fishing capacity contributes substantially to overfishing, the degradation of marine fisheries resources, the decline of food production potential, and significant economic waste. It’s no small matter, and it’s going to take an all-hands-on-deck approach to in get it under control.

The International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) has led a series of progressive workshops on the topic of capacity management, bringing together negotiators, scholars as well as representatives of Regional Fishery Management Organizations (RFMOs), industry, environmental NGOs and other international institutions. This workshop series began in 2010 with the Bellagio Conference on Sustainable Tuna Fisheries. The Bellagio Conference Report highlighted the necessity of capping the current number of vessels and discouraging the addition of new ones. The report noted, “urgent action is required. Simply put, the global growth in fishing capacity must be curtailed and fleets reduced. The time is ripe to address these problems and their root causes.”

Rights-Based Management

Success in this sense, requires significant strides in rights-based management, which means that the rights of coastal states to expand their participation in a tuna fishery must be accommodated by mechanisms designed to reduce the participation of others. Rights-based management can be used to address overcapacity, as well as conservation and management issues and goals. This may seem like an obvious concept, but the allocation of capacity and rights requires careful attention to ensure that it benefits all participants, is perceived as fair or equitable, and that it reflects the role of historical participation in the fishery and position of developing countries and coastal states.

Former Director of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), and the founding chair of ISSF’s Scientific Advisory Committee, Dr. James Joseph, wrote of the “need to address the issues related to common property resources and property-rights based management, the allocation of catches and fleet capacities among participants, the rights of access on the high seas, the authority for regional tuna organizations to deal with some of these matters.” That is precisely the next step.

Once capacity is limited, nations must work toward fairly allocating rights to existing capacity. To that end, ISSF has convened workshops to build on the Bellagio Conference Report that advance these aspects of capacity management.

The Cordoba Conference on the Allocation of Property Rights in Global Tuna Fisheries

The Cordoba Conference on the Allocation of Property Rights in Global Tuna Fisheries provided an opportunity for the participants to engage in debate and discussion in a collaborative, neutral venue on the issue of allocation of property rights and subsequent use rights in multi-lateral tuna management programs.

Concepts recognized by this conference included that the first step to allocation of rights is to close the pool of participants to which rights are allocated. I Two different levels of rights exist. The Property Right is allocated to participating states, while Use Rights are subsequently made available by those participating states to individuals or groups that operate in the fishery. In short, vessels wishing to fish within an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) (use right) must obtain permission from the coastal state (property right).

The Conference on Sustainable Fishery Agreements: Strategies for Enforcement and Compliance

The Conference on Sustainable Fishery Agreements: Strategies for Enforcement and Compliance followed, which provided an opportunity for a similarly diverse group to engage in debate and discussion on the issues of compliance and enforcement in the context of rights-based management in multilateral tuna fisheries. This is where policy development began to shine through.

The conference recognized that there was still significant work to do, and that each tuna RFMO was at a different stage in development of rights-based management and compliance and enforcement arrangements. They reiterated that these systems have to be designed with incentives to promote and encourage effective compliance, supported by effective enforcement. As some of the best minds on the issue of capacity agree on what needs to be done, it’s time for RFMOs and member nations to take capacity transfers and rights-based management more seriously.

ISSF Capacity Transfer Workshop

The outcomes of all of these workshops recognized that the issue of capacity transfers as a fundamental part of this equation and a way of accommodating coastal states’ rights. ISSF next launched the first workshop to discuss this issue – the ISSF Capacity Transfer Workshop.

The workshop articulated a number of key points, including objectives of, and options for, capacity transfer, indicators of success, and constraints and challenges. A key outcome was the recognition that capacity transfers are taking place, and that they may take many forms to meet the diverse development aspirations and choices of developing states. The workshop also identified a set of enabling factors that have contributed to the success of previous and ongoing capacity transfers, such as: stable legal and governance environments; including effective flag state control; identified property rights and security for a sufficient duration; and sustainably managed resources.

Managing Capacity

As the ISSF resolution on capacity management requires, ISSF will “continue to sponsor regional and global workshops on fleet capacity management, including mechanisms for capacity transfers.”

The first step that RFMOs must take toward managing capacity is to establish limited entry via a comprehensive closed vessel registry with an eye toward ultimately reducing the number of fishing vessels to an appropriate level.

So it’s clear that there isn’t a quick fix – there are economic, socio-economic, legal and a whole host of other factors at play when it comes to controlling capacity. ‘Fewer boats, more fish’ is a simplified way of saying it, but that doesn’t make it untrue, but let’s make sure it’s done right, without doing damage to economies across the globe or upending food security for the millions of people relying on tuna.